Peter Noorlander (lead author)

Agnieszka Raczynska, Camila Mariño and Juliana Lopes (country and region research and authors)

Storytelling is powerful and can change the world. This is particularly so for visual storytelling, which can transcend language and boundaries. Artists and storytellers are often at the forefront of social change. They can create empathy and translate sometimes complicated social demands into compelling imagery. Their stories can power movements, provide moral courage to activists and inspire and bring people together.

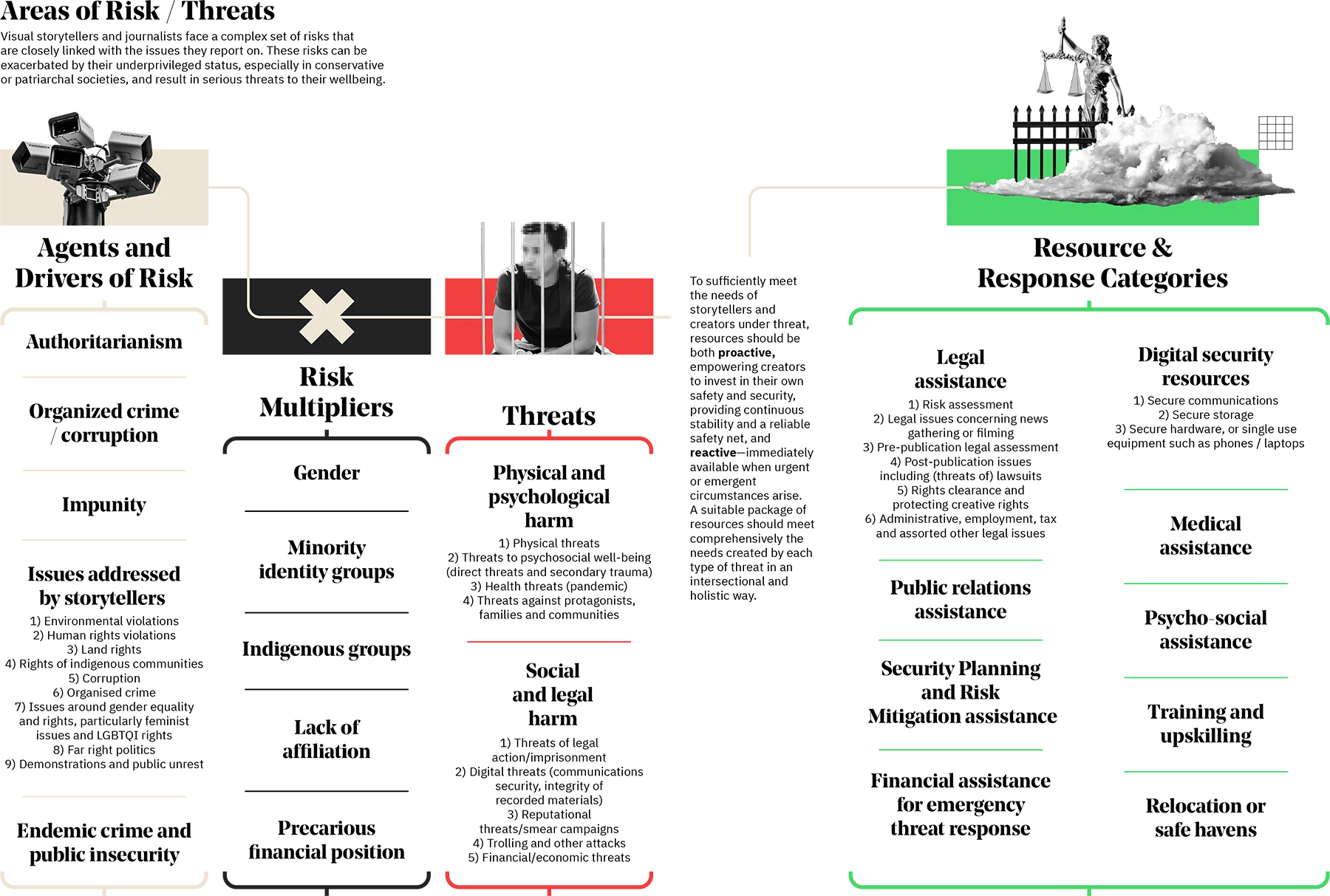

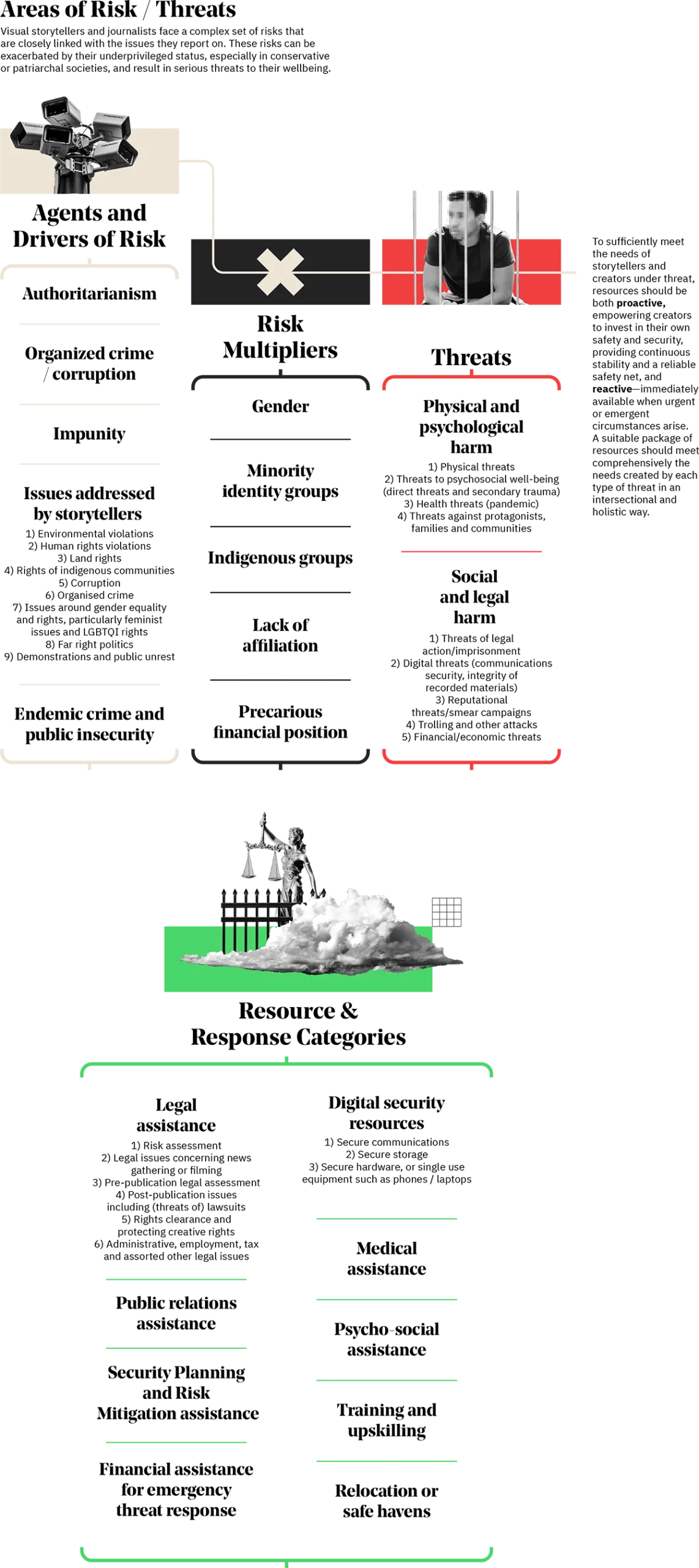

But storytelling that demands change invariably also creates risk. Those whose wrongdoing is exposed retaliate; this can take the form of threats, attacks, harassment, abuse, lawsuits, imprisonment and murder. There is a significant power asymmetry: whereas artists and storytellers often work independently or as part of small groups with few resources, those who try to silence them often have significant financial wealth or even the backing of government. Legal expenses companies might see as “pocket change” could easily bankrupt many artists.

With attacks against storytellers increasing year-on-year, concern has grown about the lack of safety and security resources available to them. This is the focus of our study. Through a series of 120 interviews with artists, filmmakers, journalists, funders, activists, academics and others, along with desk research, we have sought to identify how storytellers can be better resourced to continue to confront and speak truth to power. The study is global in its overview, with a spotlight on Central and South America where in-depth research and interviews were conducted.

“Visual storyteller” is a diverse descriptor that encompasses filmmakers, visual artists and visual journalists, among others. These are very different groups, in terms of their resources, working practices and organization. There are also strong individual differences, geographically, economically and otherwise. Some artists and journalists are widely known or are very well-resourced, others are not. Some work in a media company or as part of collectives and have a degree of protection from that affiliation, others do not. Some are in a more privileged position than others, for reasons of ethnicity, geography, gender, race, class, or otherwise. Often it is those who lack a public profile and who work alone or with only a small group of collaborators that are the most vulnerable. This scoping study is written with the more vulnerable creators in mind, but its recommendations apply across the board and their implementation will strengthen the community as a whole. Much of the research has been focused on documentary filmmakers.

Findings

In the interviews with storytellers across the world, we found remarkable similarities with regard to their safety and security situation. In many places the camera is seen as a weapon and visual storytellers and journalists face a real risk of retaliation from those who feel threatened by the stories they tell. The dangers that filmmakers are exposed to are very similar to those faced by human rights and environmental defenders who are targeted for uncovering wrongdoing and speaking truth to power. Annual reports by watchdog organizations show an increasing number of visual storytellers and their families killed, hurt, imprisoned, harassed or threatened because of their work. While not every interviewee had personally faced threats, most knew of someone who had. However, many of the filmmakers interviewed did not see themselves as at an equally high risk as human rights or land rights defenders. They downplayed risks, sometimes to a dangerous extent, and often overlooked mental wellbeing. Stress and poor self-care exacerbate other safety risks through decision-making under pressure.

Gender, socioeconomic background, sexuality, geographic origin and race are all important factors in the levels of threat experienced. Female visual storytellers are at a much higher risk than their male counterparts, a seldom acknowledged fact that few organizations are really able to respond to (although many say that they do). At the same time, much can be learned from feminist groups: they often have strong safety practices, grounded in collective safety and protection as well as in conscious self-care.

Protagonists, their families and the communities they live in are often at a higher direct risk than filmmakers, particularly with regard to possible reprisals from those whose wrongdoings they expose. Not all filmmakers were reported to take this as seriously as they should. At the same time, the publicity that protagonists gain from a documentary can sometimes act as a protective shield.

The threats faced by visual storytellers and journalists are further exacerbated by a lack of resources, particularly (and predictably) for those who lack the back-up of a large production company or media house. Very few funders are proactive about raising safety issues and funding safety resources. Visual storytellers and journalists are thus forced to fall back on protection mechanisms which are under-resourced or, in the case of publicly funded ones, lack credibility.

Our research reveals the following trends. These are overall trends, painted in broad brush strokes; of course, there are individual artists, journalists and funders who buck these trends.

There is a strong and growing international trend of attacks against the safety and security of visual storytellers and journalists. This ties in with similar attacks and violence against human rights and environmental defenders and activists, and general backsliding in respect for human rights.

There is a global pandemic of violence against women, as well as identity-based violence against indigenous groups, (sexual) minorities and others who are often at a position of disadvantage in society. Women filmmakers and visual storytellers and journalists from these communities are at particular risk.

A worryingly large number of documentary filmmakers as well as funders have low awareness of safety issues.

Visual storytellers and journalists who are safety-aware often cannot afford to invest in sufficient resources required for their protection.

Existing organizations for the protection of human rights and environmental defenders and journalists, who could in theory offer protection resources to visual storytellers, are under-resourced and by and large fail to reach them.

Conclusions: a pathway toward improvement

These findings are very concerning and pose a serious risk to the ability of visual storytellers and journalists to continue their task of reporting on and documenting issues of public concern. A lack of resources and awareness coupled with constant pressure to deliver on projects cause visual storytellers and journalists to downplay risks and underinvest in their own safety, at a time when threats to them are growing.

From the research and interviews, a clear path toward improving this situation emerged.

While little can be done about the immediate external threats—we live in a world where human rights matter less week by week—the position of those who stand up to defend rights must be strengthened. This includes storytellers, whose work can be such a powerful catalyst for broader change. A first step is acknowledgement of the issue, among funders as well as among visual storytellers, followed by a constructive dialogue to discuss what resources are needed.

Action can be taken on several fronts. First, there should be a concerted awareness-raising effort. To a worryingly large extent, there is still a lack of awareness of safety and security—among visual storytellers and journalists but also among funders. A number of artists and funders “get it,” but an equally large (or possibly larger) number don’t. We heard that this problem is greater among filmmakers than among journalists, and to address it, sustained awareness is required. There are clear opportunities for this, such as panels at film festivals and discussions in filmmakers’ forums and communities. These conversations need to be very deliberate, intentional and sustained—a few panels scattered around a couple of festivals won’t have much of an impact.

Alongside this, visual storytellers and journalists need to be empowered to invest in their own safety and security. They should be able to assess and address their own safety needs, leaving the oversubscribed organizations that provide emergency response as an absolute last resort. A number of interviewees flagged that filmmakers are reticent to initiate conversations with their funders about safety. Funders must be proactive in initiating this conversation. To help filmmakers identify safety resources, funders should ask questions: “Tell us how you have considered and implemented measures to protect the safety of your crew and any protagonists, and what contingencies you have built in to the project.” Similarly, those who fund journalists and artists—including media companies—should be proactive about protecting the employees and freelancers whose work they publish. In short, there should be a safety partnership among visual storytellers and journalists and their funders and employers. Such a partnership could extend to providing pooled services for grantees, ranging from safety training and experts to lawyers to digital security specialists and trauma counselors, as well as group insurance.

To provide an effective safety net, organizations that provide emergency assistance should be strengthened and better connected with the world of visual storytellers and journalists. While there are many—dozens in fact—every single one of them is run on a shoestring or overwhelmed with demand. They serve human rights and environmental defenders, journalists and artists who speak truth to power and whose projects put them at risk. For them, the world is a hostile environment. It’s getting worse, not better, in nearly every country. The need for emergency assistance is growing year by year.

While the emergency assistance organizations need to improve their capacity, they also need to work on outreach and connecting the different communities of artists, filmmakers, journalists and human rights and environmental defenders. Interviewees from some protection organizations told us that outreach is an ongoing and very deliberate effort, and that they try to ensure that groups and individuals most at risk know about the assistance potentially available to them. The most effective outreach is conducted in the language that those it targets operate in and builds a connection of trust. It should go beyond the usual circles in metropolitan centers; concerted efforts must be made to identify those most at risk, often in outlying areas, and reach them.

Recommendations

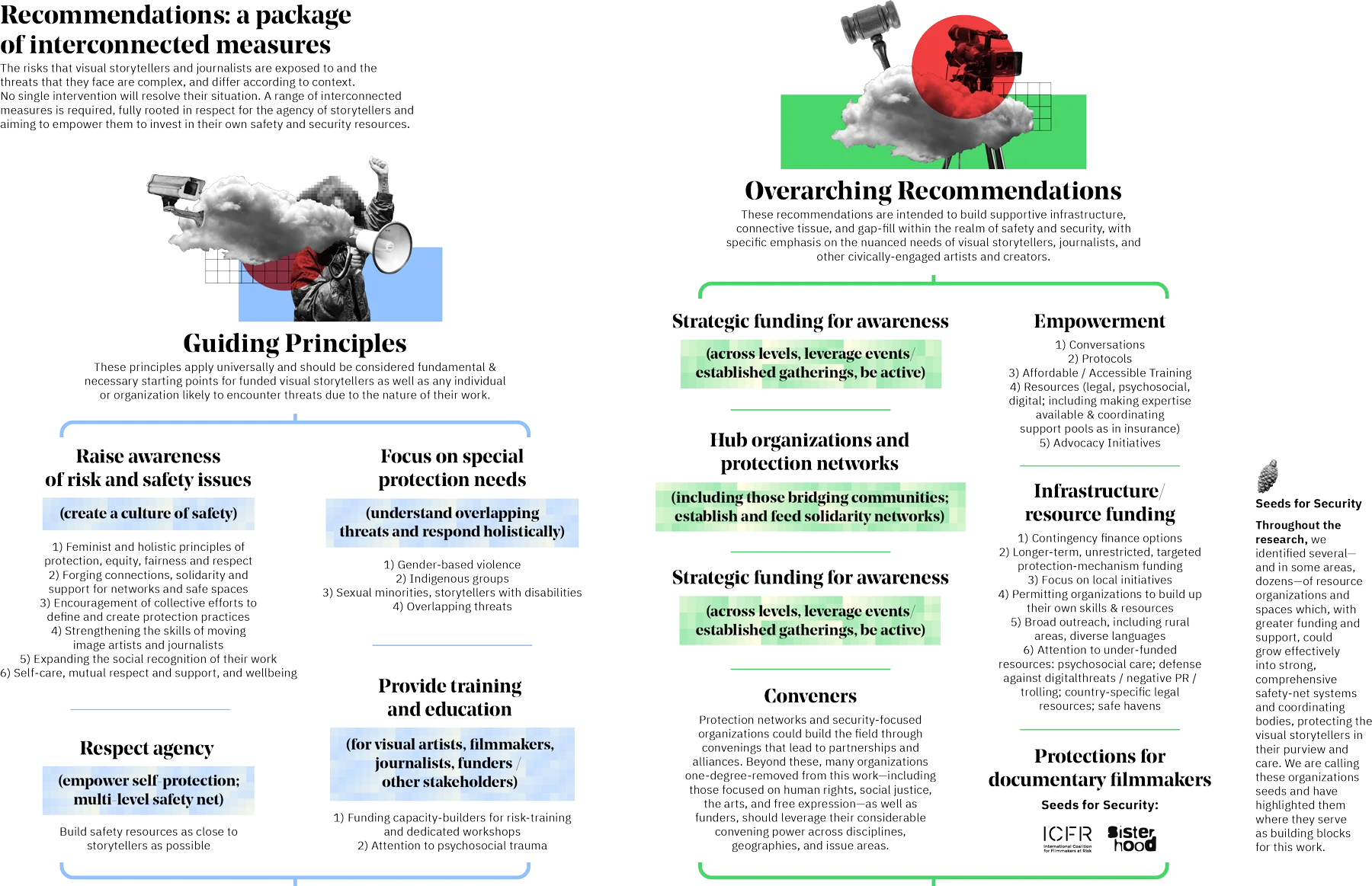

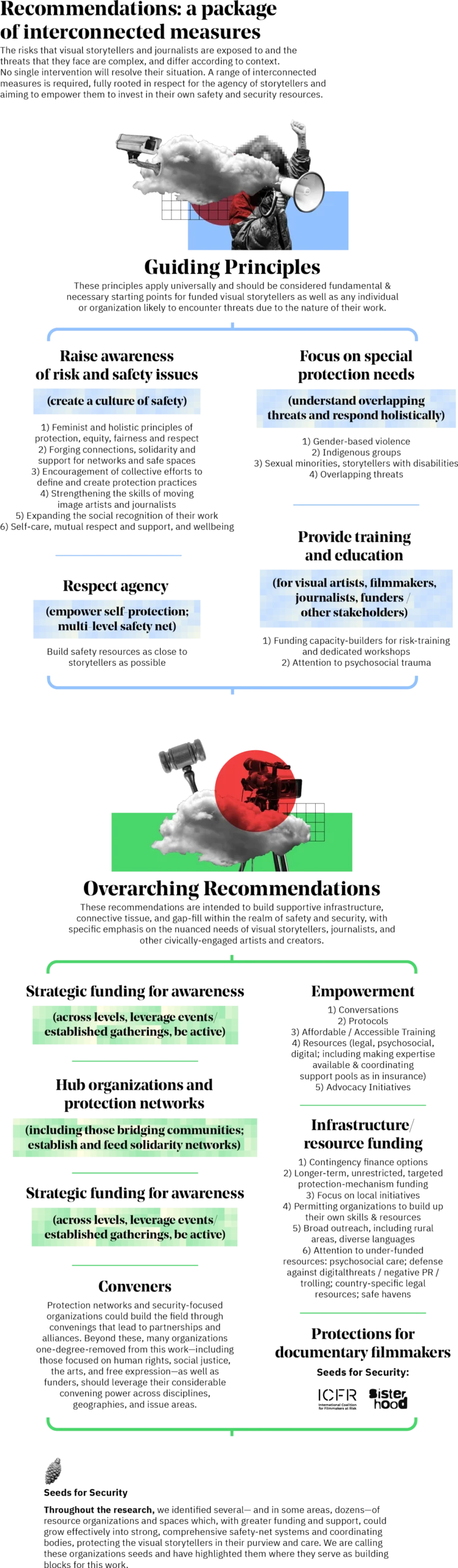

Building on these conclusions, which are grounded in the research conducted along with interview findings, we make the following recommendations. No single one of these recommendations is a silver bullet; they should be seen as a package of interconnected and related measures. The recommendations are to all funders, not just those who fund journalism and the arts. The issues described should be of concern to all social justice and human rights funders.

Guiding Principles

There are four guiding principles for any initiatives that seek to address safety and security (these principles are addressed to funders and do not replicate or seek to go over the same ground as those made in various excellent existing safety guides).

1 Raising awareness of risk and safety issues is crucial to seed the importance of the issue more widely in creative communities and connect them with protection organizations. A culture of safety should be nurtured among visual storytellers and journalists and their funders, employers and other stakeholders, centered around feminist and holistic principles of protection, equity, fairness and respect; forging connections, solidarity and support for networks and safe spaces; an encouragement of collective efforts to define and create protection practices; strengthening the skills of visual storytellers and journalists; expanding the social recognition of their work; and self-care, mutual respect and support and wellbeing.

2 Building on the awareness-raising, training and education should be made available to visual storytellers and filmmakers as well as to funders and other stakeholders. This should include funding to organizations that specialize in providing risk training and for dedicated workshops, with specific attention to psychosocial trauma, an overlooked aspect.

3 The agency of visual storytellers and journalists should be respected. In the first instance, they should be empowered to invest in their own safety and security, and that of their crews and any protagonists or communities potentially at risk. The safety net around them should be made up of local, national and international organizations and networks that specialize in safety and protection, with the role of each understood and agreed with visual storytellers and journalists. In principle, safety resources need to be built as close to the ground as possible.

4 There is a crisis of gender-based violence in countries around the world, and female visual storytellers and filmmakers face risks and threats that are different and more severe than those faced by their male colleagues. Their security needs differ from men, but there are few resources and organizations that specialize in providing protection. Funders should finance protection organizations to develop an understanding of the heightened threats and risk to safety faced by female visual storytellers and filmmakers, as well as by visual storytellers and journalists from indigenous groups, (sexual) minorities and others who are at a position of disadvantage or at heightened risk in society, and fund them to respond appropriately and holistically.

Overarching recommendations

5 Fund key organizations at the international, regional and national level to engage in a strategy to raise awareness of safety and protection issues through events (high profile as well as side events) at established gatherings such as film, journalism, arts or human rights festivals and conferences, and, as funders, take active part in that strategy.

6 Empower visual storytellers and filmmakers to have control over and invest in their own protection by:

- a Starting conversations about safety and funding safety assessments and protection or mitigation strategies for all stages of a project (including during production and after launch), separate to any other funding that is provided so grantees are clear that safety funding does not “come out of” a grant they would have received anyway. This should cover risks to physical, digital, legal and reputational safety as well as psychosocial wellbeing;

- b Promoting the use of good security protocols;

- c Making safety training tailored to the needs of visual storytellers and journalists available to all grantees at low or no cost;

- d Ensuring the availability of expertise and resources to counter legal, physical, reputational, psychosocial and digital threats, for example through retaining specialist lawyers or purchasing group insurance and making this available to grantees and funded projects (this could be pooled among several donors);

- e Supporting (advocacy for) initiatives that boost the financial sustainability of the moving image arts sector, such as a basic income.

7 Invest in resources for visual storytellers and journalists in need of urgent assistance, by:

- a Ensuring the availability of contingency finance to grantees in need (whether through a funder’s own means, by purchasing collective insurance for grantees, or otherwise);

- b Providing long-term, unrestricted funding for existing and emerging protection mechanisms that can provide emergency assistance to visual storytellers and journalists under threat. Funding should be targeted at initiatives that are as close to communities of artists and filmmakers as possible (either geographically, or because they are part of a community that is geographically dispersed but close-knit in other ways) as these are most likely to reach those in need;

- c Funding protection mechanisms to invest in their own resources, including appropriate skills for staff fielding requests;

- d Funding constant outreach by protection organizations to visual storytellers and journalists and bridging to communities outside of urban centers and in languages other than the main national language, to ensure that those at risk and in need of emergency assistance are aware of the existence of protection mechanisms and are able to place their trust in them;

- e Funding currently underfunded safety resources:

(i) resources for psychosocial care

(ii) defense against digital threats, negative PR and trolling

(iii) specialist legal resources, especially in-country

(iv) safe havens close to the regions where the threat is greatest and specifically for visual storytellers and journalists at risk (but depoliticized and styled as arts residencies, not “at risk” residencies).

8 Support hub organizations and solidarity and protection networks of and “bridges” between communities of artists, filmmakers and human and environmental rights defenders at the local, national, regional and global level, encouraging the establishment of formal and informal solidarity networks (and recognizing that keeping these networks going requires an ongoing effort).

9 Given the focus of this study on documentary filmmakers and the dearth of support specifically for them, strong consideration should be given to supporting the few fledgling efforts to provide them with protection (specifically, at the international level, the International Coalition for Filmmakers at Risk and the Sisterhood Foundation, as well as appropriate national initiatives).

10 To the Ford Foundation, as the instigator of this study: use the Foundation’s convening power, status and experience of funding in the arts, journalism and human rights to:

- a Convene other funders and bring them along on this journey toward a greater culture of safety, beginning with likeminded funders such as Luminate, IDA, IDFA, Sundance, IMS, Doc Society, Bertha Foundation, Skoll Foundation, Field of Vision, Oak Foundation and Open Society Foundations;

- b Bring together key organizations from its human rights, social justice, arts and free expression programs (including organizations that specialize in protection) to build bridges and foster connections.

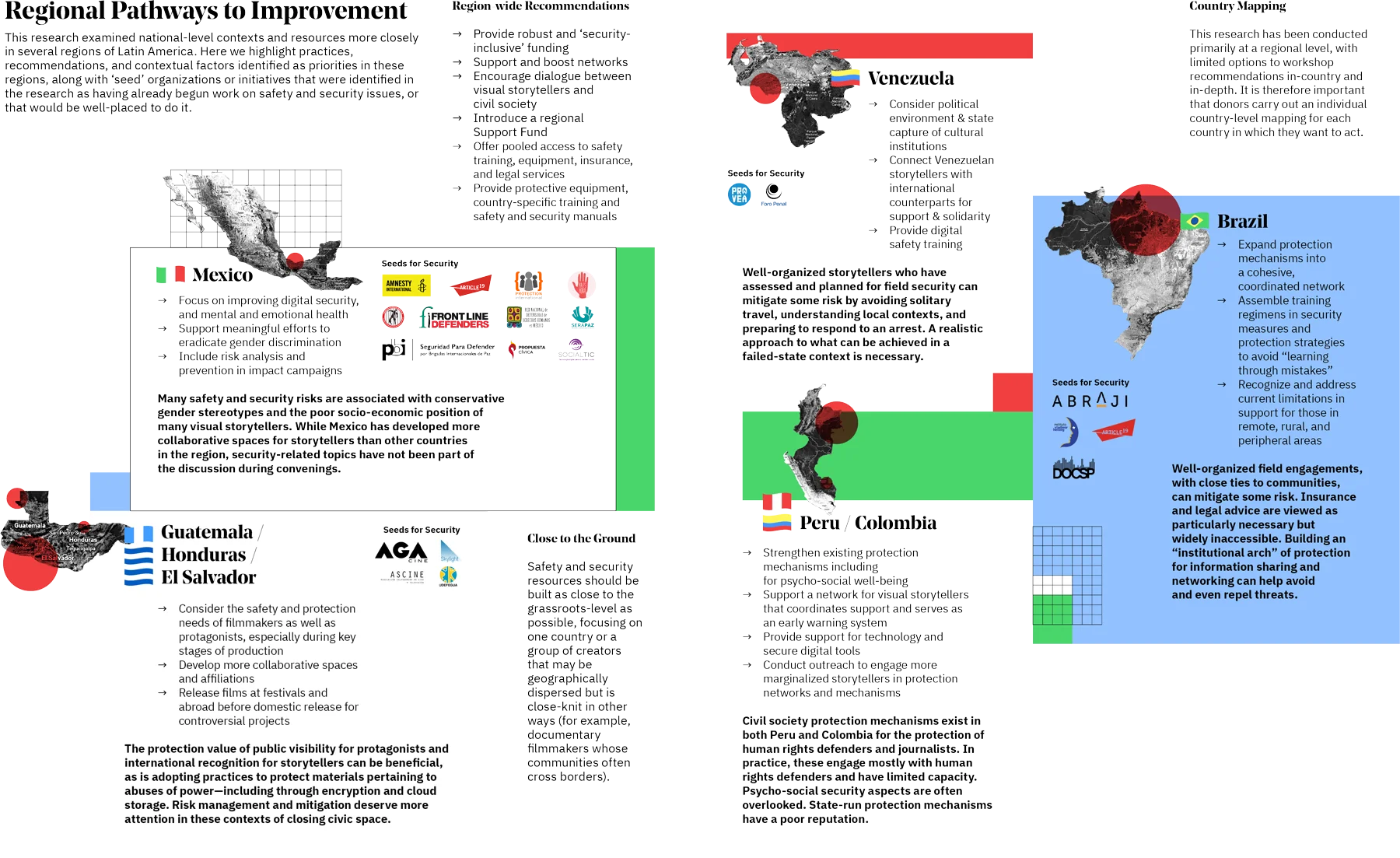

Central America, the Andes region and Brazil: pathways to improvement

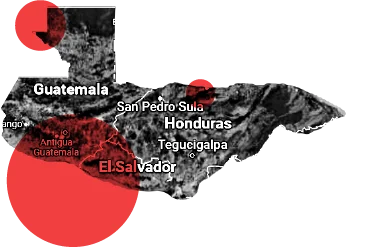

The global recommendations and findings provided in the preceding sections are informed by the research that has been conducted in the three regions studied in more detail—Central America: El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico; the Andes region: Colombia, Peru and Venezuela; and Brazil. The global findings, conclusions and recommendations are therefore entirely relevant and applicable to these countries.

The following paragraphs focus on regional and country-specific findings and recommendations. We acknowledge the need for detailed, specific and actionable recommendations. However, because—with the exception of Brazil—the research has been conducted at a regional level, there is still some specificity lacking. One of the initial recommendations is for donors to engage in an individual country-level mapping for each country where they want to act. Some interviewees have already offered to work on such an initiative (for example, UDEFEGUA in Guatemala).

There are a number of recommendations that can be made across all countries. Funders should provide robust and “security-inclusive” funding to organizations and for projects, ensuring that visual storytellers and journalists are empowered to invest in their own protection. There should be specific consideration to the situation of popular communicators and those in rural communities who are in a more vulnerable position and often unable to access funding available for “professional” filmmakers. Donor action should go beyond ensuring individual protection and look at the safety of groups and networks: of journalists, filmmakers, protagonists and their communities, as well as family members who may be at risk as a result of the work of visual storytellers and journalists. A regional Support Fund should be considered for filmmakers, journalists and human rights defenders that could be accessed in an emergency and allow for immediate safety action.

Funders should also use their resources and networks to provide discounted or group access to safety training, resources, insurance and legal services. Funders are also ideally positioned to function as a bridge between different professional communities (journalists, filmmakers, human rights and environmental defenders often work in their own silos) as well as to international markets and funding.

One of the needs and recommendations most mentioned in the interviews was training on safety, including digital security (for communications as well as the storage of material) and workshops designed specifically for women (including workshops and dialogues on gender-based violence and the exchange of best practices among the film community). Civil society organizations already active in the area of protection could be funded to offer guidance on protection and tailor their methodologies to filmmakers’ specific needs and contexts. Training should be strongly rooted in local contexts and be provided by trusted individuals or organizations (including filmmakers themselves). Training should also be pragmatic and comprise a strong “on the job” element that offers learning opportunities for creators without interrupting their production cycle.

Fostering a culture of inclusion in the film industry and preventing discrimination and harassment against women filmmakers is key to enhancing their safety. Research should be conducted to gain insights into ways to increase the participation of women, to learn from and build a gender-based and feminist approach to security and to provide support tailored to the needs of women in each country. Funders should include policies and clauses on grantees’ responsibility to prevent gender violence in grants, as well as provide specific funds to support women filmmakers’ projects.

Across and within all countries, there is a need to propel cross-sectoral connections and boost networks and spaces for collaboration, dialogue, exchange of experiences and discussion around safety. There needs to be far more frequent dialogue between documentary filmmakers and civil society organizations. Ford Foundation, with funding activities in both communities, should play an active role in engendering this.

Networks that connect filmmakers, journalists, human rights and environmental defenders and other activists across their spheres should be supported. Efforts such as SolidariLabs are powerful but require strong and sustained support (they are both labor and resource intensive). In each country, a network could be created for visual storytellers that could send alerts and function as an early warning system and also function as a central point for those in need. This can start with something as simple as an encrypted group channel and must be inclusive. In each country, more support is needed for independent film festivals, encouraging them to provide spaces for discussion and workshops, seminars and other activities focused on protection.

Visual storytellers should take time to build a relationship of trust with the communities that they visit and their leaders. More community screenings and exhibitions would be very powerful.

Specific resources that are required across the region include:

protective equipment;

country-specific handbooks on prevention and protection strategies and protocols, learning from civil society protocols, based on information obtained from documentary filmmakers and including the needs of filmmakers living in rural areas as well as crew and protagonists;

support for advocacy for law reform, focused on the main laws used to clamp down on visual storytellers and journalists (including defamation, national security, obscenity and copyright).

More collective work among visual storytellers and journalists would improve safety and lead to greater solidarity.

In Peru and Colombia, existing civil society protection mechanisms (provided by groups such as FLIP, APRODEH, CNDDHH and IDL) should be strengthened to increase their capacity to assist (including psychosocially—often overlooked) and engage in outreach to visual storytellers and journalists.

In Peru and Colombia, existing civil society protection mechanisms (provided by groups such as FLIP, APRODEH, CNDDHH and IDL) should be strengthened to increase their capacity to assist (including psychosocially—often overlooked) and engage in outreach to visual storytellers and journalists.

In Brazil, there is a strong need for coordination and expanding the geographic reach of safety mechanisms offered by civil society organizations. The organizations that currently offer safety mechanisms recognize that they are far from turning their protection efforts into a structured network. Additionally, most of the current safety mechanisms are focused on professional journalists or human rights defenders and do not reach all visual storytellers and popular communicators. This leaves a large underserved population of nonprofessional social communicators and visual storytellers outside of the urban centers—and mainly, the Rio-São Paulo axis—where most civil society organizations are based. Work has been started by the Vladimir Herzog Institute, in conjunction with other protection organizations, to convene a National Network for the Protection of Journalists and Communicators. This should be strengthened. Other groups that could take these recommendations forward include the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalists, ABRAJI, ARTICLE 19 and DocSP.

In Brazil, there is a strong need for coordination and expanding the geographic reach of safety mechanisms offered by civil society organizations. The organizations that currently offer safety mechanisms recognize that they are far from turning their protection efforts into a structured network. Additionally, most of the current safety mechanisms are focused on professional journalists or human rights defenders and do not reach all visual storytellers and popular communicators. This leaves a large underserved population of nonprofessional social communicators and visual storytellers outside of the urban centers—and mainly, the Rio-São Paulo axis—where most civil society organizations are based. Work has been started by the Vladimir Herzog Institute, in conjunction with other protection organizations, to convene a National Network for the Protection of Journalists and Communicators. This should be strengthened. Other groups that could take these recommendations forward include the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalists, ABRAJI, ARTICLE 19 and DocSP.

In Guatemala and Honduras, artists that have international recognition are less likely to face harassment. A strategy to release films at international festivals before premiering them domestically would be beneficial to safety. In Guatemala, potential conveners or facilitators of trainings include UDEFEGUA, in collaboration with Skylight and AGACINE. In El Salvador, reactivating ACINE would be a way to create a space for collaboration between filmmakers.

In Guatemala and Honduras, artists that have international recognition are less likely to face harassment. A strategy to release films at international festivals before premiering them domestically would be beneficial to safety. In Guatemala, potential conveners or facilitators of trainings include UDEFEGUA, in collaboration with Skylight and AGACINE. In El Salvador, reactivating ACINE would be a way to create a space for collaboration between filmmakers.

In Mexico, digital security and improving mental and emotional health were frequently mentioned as priorities, along with the need to eradicate gender discrimination and improve the overall socio-economic and employment conditions of filmmakers and others in the industry. Several interviewees mentioned the need to strengthen existing networks and collaborative spaces and to better connect visual storytellers with organizations that provide safety resources: ARTICLE 19, Peace Brigades International, Amnesty International Mexico, SocialTIC, Protection International, Front Line Defenders, Comité Cerezo México, SERAPAZ A.C., La Red Nacional de Defensoras de Derechos Humanos (RNDDHM) and Propuesta Cívica. #YaEsHora is a recent initiative working on gender inclusion and institutional transformation in the film industry. It has some industry support, has developed a gender protocol for the industry and aims to host panels and workshops. A further specific suggestion was made to enhance the capacity of the network of filmmakers that has sprung up in response to the current regressive public policies.

In Mexico, digital security and improving mental and emotional health were frequently mentioned as priorities, along with the need to eradicate gender discrimination and improve the overall socio-economic and employment conditions of filmmakers and others in the industry. Several interviewees mentioned the need to strengthen existing networks and collaborative spaces and to better connect visual storytellers with organizations that provide safety resources: ARTICLE 19, Peace Brigades International, Amnesty International Mexico, SocialTIC, Protection International, Front Line Defenders, Comité Cerezo México, SERAPAZ A.C., La Red Nacional de Defensoras de Derechos Humanos (RNDDHM) and Propuesta Cívica. #YaEsHora is a recent initiative working on gender inclusion and institutional transformation in the film industry. It has some industry support, has developed a gender protocol for the industry and aims to host panels and workshops. A further specific suggestion was made to enhance the capacity of the network of filmmakers that has sprung up in response to the current regressive public policies.

A donor strategy to further the protection and safety of visual storytellers in Venezuela needs to take very specific account of the challenging political environment, in particular the politicization and capture by the state of cultural institutions, and be realistic about what can be achieved. Specific actions could include:

A donor strategy to further the protection and safety of visual storytellers in Venezuela needs to take very specific account of the challenging political environment, in particular the politicization and capture by the state of cultural institutions, and be realistic about what can be achieved. Specific actions could include:

- 1 provide general support to strengthen the few existing human rights organizations in the country (PROVEA and Foro Penal) and enable them to assist visual storytellers;

- 2 connect independent visual storytellers with their counterparts internationally, developing a network for support, solidarity and group protection;

- 3 organize trainings on digital safety, led by independent filmmakers and possibly hosted by organizations, very carefully chosen, given the politicization mentioned above.